Energy: A necessary evil?

In Canada, there are over 10 mines north of the 55th parallel producing their own power. In Africa, most mines are also self-sufficient. While the main objective of these mines is to extract and process minerals, power plant operations must now be added to their portfolio.

Typically, power plant operations represent 15% of a mine’s total operating costs and up to 75% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Instead of viewing the plant as a necessary evil, why not shift the paradigm and view it as a wealth of opportunity?

Opportunities

The Agnico Eagle Mines Meadowbank mine is a perfect example of a mine that has explored the potential of optimizing its power plant. Generating annual savings of $2.5 million and 2 million litres of diesel consumption, this optimization has resulted in a 5,500-tonne reduction in GHGs.

Where to start to achieve such performance? First, when a plant is being designed, a number of technology solutions can help reduce operating costs:

Generators

This is still the most popular technology because of its reliability, quick response time, efficiency and heat recovery simplicity. It is possible to opt for a model with a lower rotation speed (720 or 514 revolutions per minute (rpm)) to improve efficiency and reduce maintenance costs. Depending on the model, savings of up to 15% in fuel consumption can be generated compared with a 1,800-rpm generator.

Variable speed generators are increasingly available on the market. They are able to maintain a relatively constant frequency regardless of load.

Heat recovery

Rather than heating with electricity or a boiler, large amounts of energy can be recovered from generators, via both the engine and the exhaust gas. An optimized system can produce an additional 0.85 kW of thermal energy per electric kW.

Renewable energy

Wind turbine manufacturers are gaining more and more experience in the Arctic, with their portfolio of projects increasing every day. Consider the De Beers Diavik mine (four turbines) and the Glencore Raglan mine (one turbine), for example. These sites are seeing an annual reduction of close to 6 million litres of diesel consumption.

While the Arctic’s average solar intensity is not exceptional and may be non-existent in winter, the option to install photovoltaic panels can be cost-effective, considering that fuel costs are high in outlying regions. For example, a research centre in Kuujjuaq recently installed a new 50 kW solar panel farm.

Batteries

Linking batteries with renewable energy technology optimizes their use. This enables generators to operate at optimal efficiency, by mitigating variations from wind turbines and PV panels, as well as from the system load.

The standard fuel used for remote northern sites is Arctic diesel, which is more expensive and contains less power than regular diesel. However, since Arctic diesel is required only during cold snaps, regular diesel is used in summer, resulting in energy cost savings of approximately 4%.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is also an option for remote sites. The use of LNG helps reduce GHG and smog-causing NOx emissions by 25% and 80% respectively.

Lastly, another optimization opportunity for a power plant lies in its operating strategy. It is not unusual to see plants using generators with a small load factor (< 80%) to protect themselves from outages. But a properly optimized and maintained plant using a load shedding system is able to operate at a higher load factor (> 90%), thereby improving efficiency and limiting the number of generators running.

Agnico Eagle’s Meliadine mine

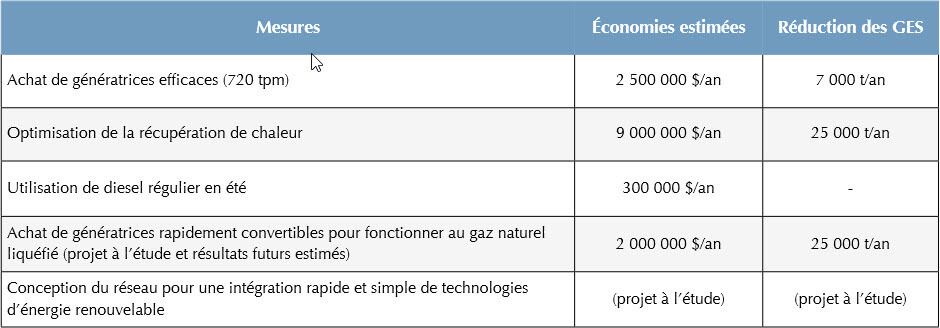

With lessons learned from its first plant at the Meadowbank mine, Agnico Eagle has placed greater emphasis on the design of the future power plant at the Meliadine mine, implementing a number of optimization measures. Table 1 outlines some of these measures.